Genius of the Place

What does going to the park mean to you? Do you have high expectations of what an experience at the park should contribute to you and your family’s life?

City parks are probably the most obvious example of citizen owned public spaces, yet they can offer very different experiences depending on their location, size, design, accessibility, activation, and stewardship. At the margins, public parks can be places of great beauty, inspiration, and human connection or equally spiritless, foreboding and antiseptic. At the start of this decade, America’s 100 largest cities added 120 new parks according to the Trust for Public Lands. That amounts to dozens of new communities that had the opportunity to get it close enough to right to fall into the former category.

In the second edition of the book Great City Parks, a comparative study of 30 of North America and Western Europe’s most impressive public spaces, author Alan Tate asks the question ”what might constitute a great park? There is no easy answer. Well, there is. It’s like being in love. You know it when you’re in it”. I tend to agree with that simple sentiment but know that a lot of dedication, attention and skill goes into the creation of the places that we love.

Frederick Law Olmstead, an American giant of landscape architecture and a primary designer of New York City’s Central Park took the design of parks and green public spaces very seriously. Before Olmstead and his partner Calvert Vaux entered the Central Park scene in the 1850’s, there were very few parks of any scale or significance in major American cities. During that time, the idea of significant public green spaces was thought to be a European concept.

Greenswald: Olmstead and Vaux's awards winning design for Central Park (NY Historical Society)

Olmstead biographer Charles Beveridge notes that Olmstead and Vaux, in their work on Central Park, created for perhaps the first time in America, “the kind of park that was both a gathering place for people, a promoter of community, and created the kinds of landscapes that were, they thought, a medical antidote to the rush and the sound and the hard edge and all of the city”. (NPR Olmstead’s Legacy: Parks for the City).

Olmstead believed that the design of public spaces could and should have great utility beyond just resulting in lovely places. He knew that at the end of the day the owners of the park - the citizens, deserved a special place that contributed to the quality of their lives.

In addition to his seminal work with Central Park, Olmstead went on to create or contribute to the design of some of North America’s greatest parks and public spaces. Examples in America are Brooklyn’s Prospect and Fort Greene Parks, Boston’s Emerald Necklace, the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, the grounds of the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C., and the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. In our neighbor to the north, Olmstead designed Mount Royal Park in Montreal. It would not be a reach to say that Olmstead’s has contributed to the design of thousands of the parks and green spaces that dot cities and towns throughout North America – either directly or through his influence. He was a deeply civic-minded man whose ideas of public space design were aimed to make public spaces special, inspirational and worthy of the citizens who owned them. Among his most interesting ideas are:

1. Respect the Genius of the Place.

Olmstead believed that the purpose of park design was to offer citizens “greater enjoyment of scenery that they could otherwise have consistently with convenience within a given space”. But he held fast to the idea that designs should remain true to their natural surroundings, and not battle with them. This philosophy was rooted from the teachings of eighteenth century writers on landscape art like Humphry Repton, one of the great designers of the century who believed that “all rational improvement of grounds is necessarily founded on a due attention to the character and situation of the place to be improved”.

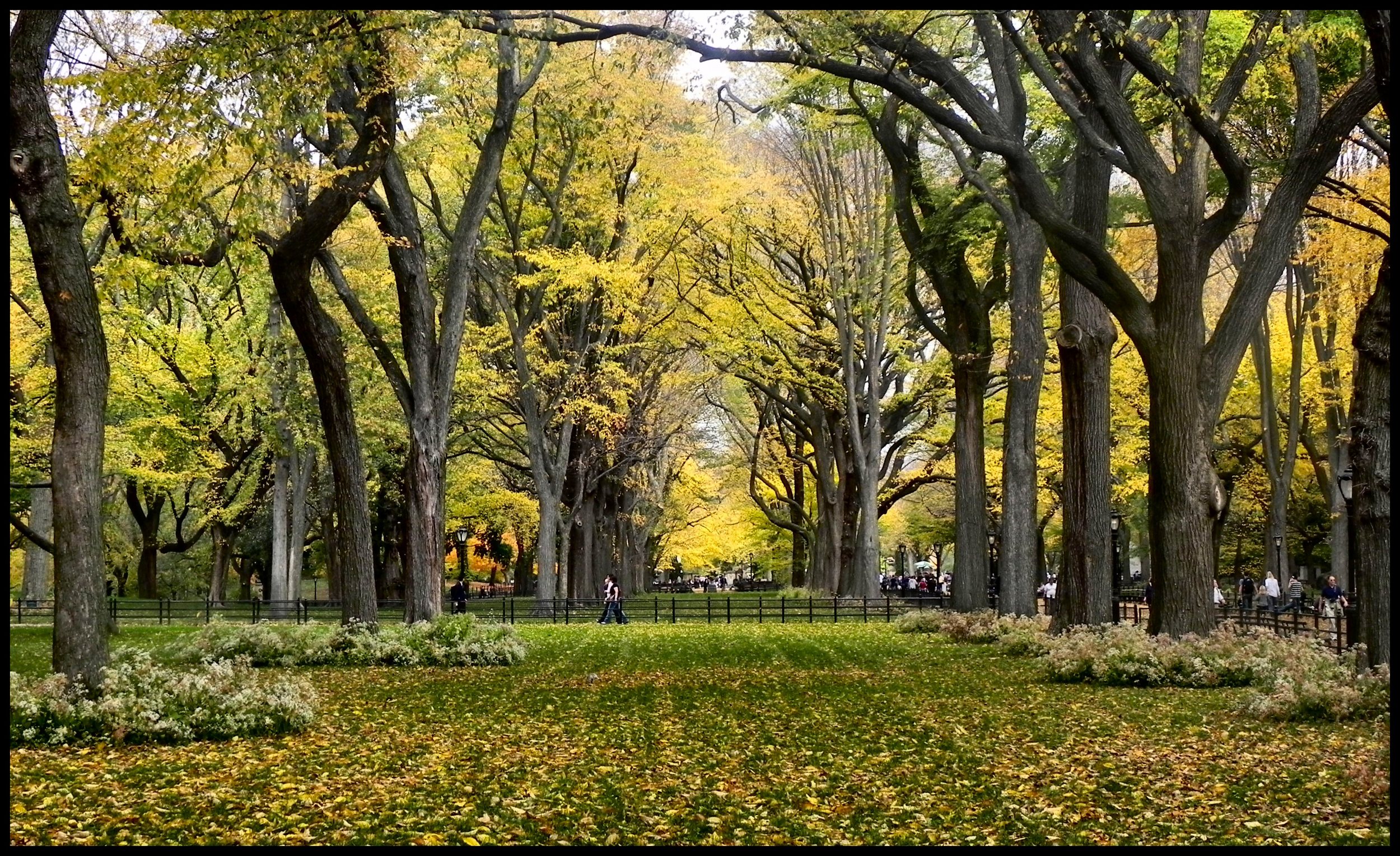

Central Park

2. Subordinate Details to the Whole

In Olmstead’s designs, there was little room for details that were to be viewed as stand alone individual elements. In his work, they were always threads within a larger fabric. He felt that what separated his work from a gardener’s was “the elegance of design,” (meaning the designer should subordinate all elements to the overall design and to the “big Idea”). Olmstead was a true champion of context. He warned against thinking “of trees, of turf, water, rocks, bridges, as things of beauty in themselves.” In his work, these elements were threads in a larger fabric. He avoided overly decorative plantings and structures in favor of a landscape that appeared organic and true. He was a big picture man, and for him, the big picture of the design controlled.

3. The Art is to Conceal Art

For Olmsted, the goal in park design wasn’t to make park goers “see” his work. In fact, it was to make them unaware of it. To him, the art was to conceal art. And the way to accomplish this was to remove distractions and demands on the conscious mind. Park goers weren’t supposed to be obligated to examine or analyze parts of the scene. They were supposed to be unaware of those elements working in concert on their behalf.

Olmsted’s works appear so natural that one critic wrote, “One thinks of them as something not put there by artifice but merely preserved by happenstance”. (Matt Linderman, Signal Noise). I have similar feelings when strolling along segments of New York’s High Line Park

The High Line in NYC (Timothy Schenck)

4. Unconscious Influence

The ideas of Horace Bushnell, a religious writer, on “unconscious influence” in people affected Olmstead’s design philosophy. Bushnell believed a person’s real character couldn’t be expressed verbally, but instead was revealed at a level below consciousness. Olmsted applied this idea to his landscape designs and wanted his parks to create an unconscious process that produced relaxation or an “unbending” of a mind tightened by the stresses and artificiality of city life. So he worked hard to remove distractions and demands on the conscious mind of the park goer. When visiting an Olmstead designed park, you might observe that his designs subtly direct movement throughout the landscape. Park goers are led without realizing they’re being led. Central Park and Mount Royal both offers strong examples of that experience.

Prospect Park in Brooklyn USA (USGS)

5. Avoiding Becoming a Slave to Fashion

Olmsted also rejected displays “of novelty, of fashion, of scientific or virtuoso inclinations and of decoration.” He felt popular trends of the day, like specimen planting and flower bedding of exotics, often intruded more than they helped.

For example, he contrasted the effect of a common wild flower on a grassy bank with that of a showy hybrid of the same genus, imported from Japan and blooming under glass in an enameled vase. The hybrid would draw immediate attention, he observed, but “the former, while we have passed it by without stopping, and while it has not interrupted our conversation or called for remark, may possibly, with other objects of the same class, have touched us more, may have come home to us more, may have had a more soothing and refreshing sanitary influence”.

I love the story of Olmstead describing his response to the beauty of parts of the Isle of Wight during his first trip to England in 1850, where he recalled, "Gradually and silently the charm comes over us; we know not exactly where or how." One could not seek that feeling too directly, however. "Dame Nature is a gentlewoman," he cautioned, "No guide's fee will obtain you her favor, no abrupt demand; hardly will she bear questioning, or direct, curious gazing at her beauty" Beveridge, Olmstead – His Essential Theory).

Mount Royal Park in Montreal

These are just a few of Olmstead’s many ideas on how the design of parks and green spaces should contribute to lives of those that experience them. I appreciate the thoughtfulness with which he approached his work and believe that commitment has contributed to the durability and irresistibility of the places that he helped create generations ago. I also hope that as citizen owners and designers we can hold ourselves to an equal standard of thoughtfulness and respect for context in the future design and development of those American parks yet to be imagined.