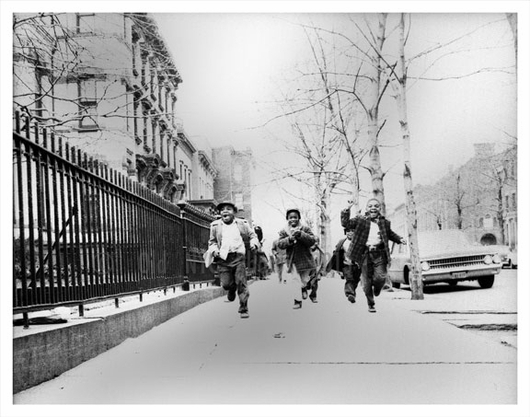

Playing in the Street

I grew up in the old city of Hampton, Virginia, located on a narrow peninsula in the southeastern area of the state. In any direction from our home, we were minutes from the rocky banks of the Chesapeake Bay, the marshy edges of the James, Hampton, and Back Rivers, or the muddy fingers of any number of neighborhood creeks. I hope, but doubt that I appreciated our close proximity to fresh flowing water then as I do now. The physical beauty of that community was an asset, but as a kid, I appreciated something else even more – the streets.

As youngsters, my brother, sister, friends and I walked a lot, especially after school and during the summers. We expertly used the well-connected network of sidewalks and narrow slow moving streets to help us explore our Greater Wythe neighborhood and those beyond it. Up until the moment the streetlights came on, we were generally allowed to explore the neighborhood and we took full advantage of that freedom.

Like millions of the kids of our generation in cities and towns of every size across America, we converted as much of the public right of way as possible into our personal and informal playground. Also, any nearby vacant lot was subject to being co-opted and repurposed for softball, kickball or dodgeball. Its amazing how a group of kids can have enough imagination to lay out bases and create both an infield and an outfield on a small weedy lot.

We learned how to transform our small neighborhood streets into whatever they needed to be for our entertainment each day. We played marathon tag football games between the curbs. We yelled “CAR!” when a vehicle came bending onto the block, flowed to the side as it passed, then flowed back into the streets just as the waters of the bay did blocks away when a ship passed.

In our early teens, we crowded under the midblock streetlights on many hot, muggy nights. There we talked, teased, joked, danced and spun around on folded cardboard boxes to the portable boom box driven sounds of “emerging” artists like Prince, Run DMC, and LL Cool J. As night pressed on and our parents wanted us closer to home, we often migrated to one friend's front yard or tiny porch until one by one we were called in for the night.

To us, the neighborhood streets and sidewalks felt safe, as if they were built primarily for our recreation. Yes, the cars were always there, and always moving, but it seemed as if they were on a different plane. We saw them and avoided them but they didn’t really appear as a threat to our safety on those small streets. Rare was the parent who took exception to our chosen field of play. The rare examples of accidents between car and kid happened when a football or the occasional clumsy player (like me) collided with a parked car minding its own business. I don’t know why things appear so much more perilous these days. Perhaps the same small streets carry a greater number of cars, or maybe cars simply move much faster along them today. If speeds have increased, I would wager they are partially the result of the “children likely at play gene” being squeezed out of our collective driver's DNA.

In his book Walkable City, Jeff Speck calls out his Ten Steps of Walkability. Among them is: Protect the Pedestrian. The elements of street design that form this step include block length, lane width, turning motions, direction of flow, signalization, and roadway geometry. I did not make a special trip home to analyze how the streets in my old Hampton neighborhood fared on this test, but I do know that it felt pretty right when walked them as a kid. The design got it right as far as we were concerned.

Our city had nice parks and ample ball fields, and some were within walking distance, but none seemed to offer the dynamic and spontaneous experiences we were offered when “playing in the street”. In her biting seminal book, the Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs writes of the value of the many forms of sidewalk play compared to the exclusive use of neighborhood parks for recreation.

“It is not in the nature of things to go somewhere formally to do them by plan, officially. Part of their charm is the accompanying sense of freedom to roam up and down the sidewalks, a different matter from being boxed into a preserve”.

Check out this short video from The Play Out Group in the U.K. on their work to create regular and safe opportunities for young people to play in the street in our modern world and what it might mean to both child and parent.

For us, the ball, the bat or the cardboard box did not have much competition for our attention because there was no equivalent to today’s ubiquitous Xbox, PlayStation, iPad, or smartphone. So after school, we were all quickly back outside connecting with each other and the world around us - as if we hadn’t just been together all day at school.

Our neighbors were not passive acquaintances, but more often than not, family friends. We knew them and they knew us. For example, next door to us lived our friend Ronald and his sister Tonya. It seemed as if these two had more cousins within walking distance than all of the other neighborhood kids combined. This meant that we always had enough players for a game of football, softball, and basketball or enough soldiers to defend our block from periodic “dirt bomb” attacks from “friends” outside our neighborhood. The block was almost always full of kids, and we were almost always outside.

I wonder how kids living today in that same neighborhood, or in the many thousands of others across America might see and experience the world immediately around the place they call home compared to the experiences of their parents a generation earlier. Here in our home base of San Antonio, Texas, my 11 year-old son James loves to travel along our neighborhood's sidewalks, but if you asked him why enjoys it he would tell you it’s primarily for the purpose of exploration. For him, walking the neighborhood on those sidewalks allows him to see subtle and interesting elements of his world that might otherwise be overlooked through the blur of a car window. He doesn’t however, seem to assign much additional value to the sidewalks as a potential way to engage and connect with friends, or to entertain himself.

So, despite the fact that relative to the rest of our city, James and I reside in a very walkable and pedestrian friendly neighborhood, his first inclination is not to turn to the outside for his entertainment and engagement with others. That need seems to be comfortably satisfied by a black game controller, headphones and a mic and through a steady stream emoji texting via iPad.

Perhaps that is just an evolution in the way some young people experience their neighborhoods and simply something for me to reluctantly but helplessly accept - sort of like texting versus talking. Either way, I can't help but feel both nostalgic and a little sad that for all the richness in the recreational lives of our young people these days, some may never fall in love with "playing in the street".